Overcoming Structural Challenges: The Journey of Jamaican Music to International Recognition

- Dennis Howard

- Apr 25, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2023

For decades, Jamaican music has been recognised for its addictive riddims, infectious melodies, and thought-provoking lyrics. Despite its rich cultural past and the celebrated success of the music since mento. It might surprise you that Jamaican hit songs take a long time to attain international recognition, especially compared to big singles in the UK and the US in genres such as hip-hop and pop.

This disparity may be found in the sales data for some of Jamaica's most well-known songs. For example, six years after its first release in 2013, Karnium's "Nobody Have to Know" only achieved gold certification in September 2019. Similarly, although considered a classic in Jamaican music, Buju Banton's album "Til Shiloh" took 24 years to gain gold certification in 2019.

Even Gregory Isaacs' classic record "Night Nurse," published in 1982, only achieved silver certification in the UK in 2021, over 40 years later. After making its UK debut in 1998, Mr. Vegas' "Heads High" sold over 200,000 copies. It reached this milestone in 2021, twenty-three years later.

However, it took several years to achieve this UK milestone in 2021.

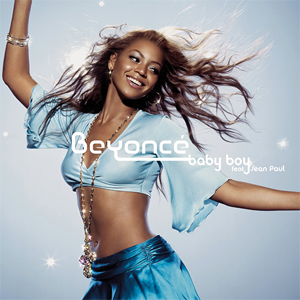

One of the most recent examples is Wayne Wonder's "No Letting Go," released in 2002 but achieved gold certification in the United States only in 2022 after selling 500,000 units. "Baby Boy," Beyonce's collaboration with Sean Paul, took a long time to obtain recognition, with the tune receiving Brit certification in 2023, 20 years after its debut in 2003.

It is evident from the data that the sales don't match up with the hype of Jamaican-produced reggae and dancehall. What accounts for this? The possible reasons are many and complex, but let me untangle some of the more salient ones. There are also various structural reasons why Jamaican music may take longer to gain international attention. Here are a couple of such examples.

Marketing to who

We must remember that Jamaican music is considered imported music which the major labels in the United States do not widely handle.

With streaming, it is potentially easier for our music to reach an international market with the disintermediation of the distribution chain. However, marketing is even more critical due to this levelling of the field in digital distribution. Record labels in the United Kingdom and the United States have significant funds to market their artists and songs, which can quickly catapult them to the top of the charts. On the other hand, the Jamaican music industry operates on a considerably smaller scale, with fewer resources available for promotion and distribution.

Outfits like VP Records and Greensleeves Records and distributors/aggregators such as Zojak, Dubbshot and Hapilous cannot compete with the budgets available to the major record labels owned by mega conglomerates. As a result of limited marketing and distribution resources, it may take longer for their songs to reach a bigger audience. For example, the late Jamaican reggae artist Garnett Silk made multiple albums in the 1990s, but his music acquired considerable international acclaim only after his sad death in 1994

Airplay

Airplay access is another big obstacle for Jamaican imports; urban radio stations in the US and the UK are the outlets for Jamaican music. However, in typical ethnocentric consumer tendencies, radio programmers restrict the number of Jamaican songs they will continue to add to their rotation. Even Jamaican-friendly stations like Hot 97 in New York (holds a 2.2 share of the market) and 1 Xtra (under a million listeners nationally) have reduced the number of songs allowed in general rotation. Leaving Jamaican content to a smaller audience of specialist shows that usually air on weekends.

Summer Me Bad

Another issue is the seasonality of Jamaican music rotation on radio in the US market, the largest music market globally. Programmers are only interested in the music as a "summer fling". As Joe Coscarelli noted, "More often, Caribbean dance music has been a summer fling — one-off hits by largely anonymous acts that, for a time, fill playlists for barbecues and boom from cars but rarely result in sustainable stateside careers."

Jamaican music outside Jamaica may not always garner significant airplay on mainstream radio and television stations. This can make it more difficult for Jamaican musicians to gain exposure and develop a fan base. Vybz Kartel considered dancehall royalty in Jamaica, and the Diaspora is rarely heard on radio stations or widely known outside of Jamaica is one example of this. Despite his popularity in Jamaica, he has struggled to gain considerable international crossover success. a fact that has his superfans in disbelief. yet no one can doubt the influence of Vybz Kartel, but in terms of numbers and commercial success internationally, that's a non-starter.

.

Language and cultural barriers

Jamaican music is frequently performed in Jamaican Patois, a dialect that non-native speakers may find difficult to understand. While learning Jamaican is becoming one of the hippest and coolest things to do globally, more and more artists from North America, Africa, Japan, and the UK are adopting the Jamaican vernacular. The system conveniently uses it as an impediment to mainstream access. Furthermore, Jamaican music's cultural references and nuances may only sometimes translate effectively to audiences outside Jamaica.

For example, Chaka Demus & Pliers' dancehall hit "Murder She Wrote" was a major smash in Jamaica and the United Kingdom, reaching number 27 on the UK Singles Chart in early 1994, but had middling success in the United States, peaking at number 57 on the US Billboard Hot 100, spending 17 weeks there. Their biggest song was "Twist and Shout," a remake of the Top notes and Isley Brothers hit, which peaked at number one in the UK for two weeks. the song was also charted by the Beatles but peaked at 48 in the UK in 2010.

A Question of Definition

Another crucial factor to consider in the identity crisis that Jamaican popular music is mired in. Since the 2000s, music production has evolved significantly, and as a result, the music has changed, which necessitates the labelling of new genres. My work has identified three distinctive genre-changing moments since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

It started with the fusion period, where dancehall was fused with genres such as soca, hip hop, r&b, salsa and bhangra, among others; this resulted in songs such as "Murder She Wrote" (Chaka Demus and Pliers), "Housecall" (Shabba Ranks Maxi Priest), "Slow and Sexy" (Shabba Ranks and Johnny Gil), "Romantic Call" (Patra and Yo-Yo).

This period was characterised by the new genres I have labelled one beat; This period was led by production outfits such as Sean Nizzle, Scatta Burell, Don Corleon, Steven Mcgregor and Dasceca. The music evolved from the minimalist beats of dancehall to a fusion of many divergent styles, such as salsa and Indian pop and familiar genres, such as synth-pop, hip hop, r&b and jazz, blended with traditional Jamaican sounds.

The third and current phase is still up for classification; it is labelled trap dancehall, traphall and tropical house, which emerged from the Omi "Cheer Leader" period.

The debate has been robust and passionate, with traditionalists urging sticking to the known and upstarts declaring no looking back. It's our time. The tragedy is that while the discourse is ongoing, we are missing many opportunities to polish, fine-tune rebrands and market these new sounds to an international market, which is always looking for new trends.

The Need for a Music Ecosystem

The lack of a well-structured music ecosystem is also at the root of the lack of cohesiveness in the Jamaican music industry. The music organisations are all underfunded, weak, lack capacity and need more basic infrastructure. The government needs the will to support and encourage the development of a sustainable music ecosystem.

Creativity or the lack of it

The main issue currently is the lack of creativity in popular music, which is blocking access to the music industry's marketing behemoth. Jamaican popular music is mostly about scamming (known in Jamaica as chopping), obeah, guns and consumerism. The music has descended into subgenres that I call "gloom sound" and " dark side". While there is still some level of creativity present example Shane O's "Dark Room" there are some promising artists such as Chronic Law, Nation Boss, Yaksta and Valiant and Skillibeng.

Missing are girl tunes, danceable beats, happy music and sufficient new acts that have the total package required for international stardom. The current themes are going to fail to crossover into a mainstream market. However, it will be hard to tell the new crop of artists to change due to the financial rewards they are reaping due to the unique structure of the Jamaican music ecosystem.

The main income stream for our music is live shows and dubplate recordings for sound systems. All that is needed is a popular song in Jamaica and the diaspora. Usually promoted through social media marketing, an artist could make millions in Jamaican currency and hundreds of thousands in US currency.

Once an artist has made this jump, it will take a lot of work to suggest a change in strategy to attract a bigger market, especially when the management is not up to standard to guide the career to international status. These are only a few structural reasons why Jamaican music may take longer to gain international sales awareness.

Final Thoughts

Despite these obstacles, Jamaican music is a thriving and significant component of the global music scene. Popular Jamaican music genres such as reggae and dancehall may have devoted followings in particular regions of the world. Still, they may have a different mainstream appeal than other genres, such as pop or hip-hop. Reggae acts such Jr Gong and deejays such as Sean Paul, for example, are revered in Jamaica and have a devoted international following and have had very successful careers. Still, they have never attained the same popular and commercial success as pop musicians like Beyonce or Justin Bieber. To put it diplomatically, the system is not structured to facilitate that kind of achievement for Jamaican superstars.

Jamaican popular music remains a source of pride for the country and its people. The distinctive blend of reggae, dancehall, dub and other genres such as one beat, trap dancehall, and r&b fusion has influenced innumerable musicians and music scenes worldwide. Its impact can be heard in everything from hip-hop to pop music and afrobeats. While Jamaican popular music may take longer to attain international recognition, its significance is evident. It has grabbed listeners worldwide with its addictive beats and profound sentiments, leaving an enduring influence on the music business.